Museums through Prof. Thapar’s eyes

Source: The Island

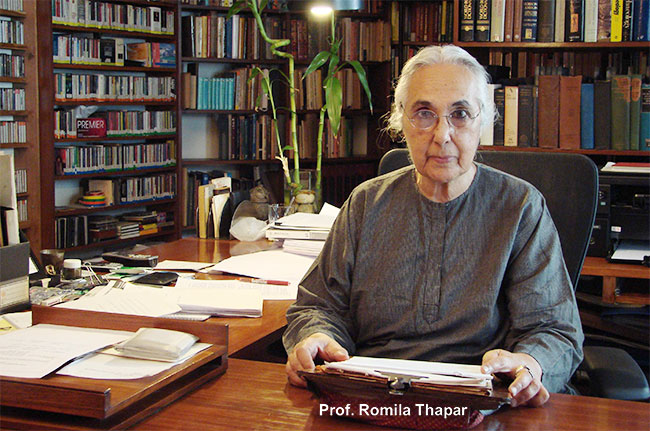

On Thursday, 27 January, Prof. Romila Thapar will deliver the Dr Roland Silva Memorial Lecture to the National Trust of Sri Lanka. Prof. Thapar will be speaking about the museums in India, charting their evolution from private collections to public displays and placing them in the context of similar institutions from other colonial societies.

Museums formed a crucial part of the colonial project, aiding administrators, officials, scholars as well as nationalist elites in their reconstructions of the countries they lived in and governed. Not surprisingly, after Independence the role of such institutions changed. Prof. Thapar would be discussing this aspect as well along with their potential to bring the historian and the social scientist together and their contribution to society.

The event will be the 141st such organised by the National Trust, as part of its Monthly Lecture Sessions. Originally held on the last Thursday of every month at the HNB Auditorium in Colombo, these lectures have brought in various scholars from fields connected to the study of history including archaeology, architecture, and ornithology. The shift online during the COVID-19 pandemic did not bring them to a halt: while the trustees held 10 online lectures in 2019, they held eight in 2020 and another 10 in 2021. Since 2015, moreover, these lectures have all been uploaded online free for everyone and anyone.

The brainchild of two of Sri Lanka’s finest archaeologists and scholars, the National Trust of Sri Lanka celebrates its 17th anniversary this year. Its objectives include the identification, documentation, protection, and conservation of the country’s heritage, defined in terms of physical objects like historic buildings, monuments, artistic and cultural works, as well as intangible artefacts like rituals, customs, and beliefs. More importantly, it seeks to inculcate an interest in these matters among ordinary people.

There it has more or less been doing what such organisations should be doing. The contemporary notion of a National Trust first came into being in late 19th century in Britain, with the establishment of a National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. Founded as a not-for-profit association in 1895 and incorporated by an Act in 1907, it has since become the largest conservation charity in Europe. Its aim has not just been to save important sites from destruction, but also to open them up for public enjoyment. More than 125 years later, it has evolved into a fully-fledged institution, overseeing more than 500 historic sites, 250,000 hectares of land, and 780 miles of coastline.

Since then similar institutions have sprung up elsewhere. In India, a National Trust was established as a registered society, a corporate body with its legal personality, in 1984. Today that country is home to more than one such society: the International National Trusts Organisation lists three, including the Indian Trust for Rural Heritage and Development. In other countries these organisations serve different functions: the Yangon Heritage Trust, for instance, focuses on urban heritage, while the Siam Society also focuses on the natural sciences. Whatever function they serve, the International National Trusts Organisation lists more than 80 of these institutions, emphasising their common inheritance.

Though the need for a National Trust had been felt for some time in Sri Lanka, nothing was done about it until Roland Silva and Senake Bandaranayake intervened in 2004. The concept papers reveal that a great deal of thought went into the founding of the organisation. Initially conceived as the “Sri Lanka National Heritage Trust”, it later transformed into the National Trust for Cultural and Natural Heritage. The concept papers tell us that from its inception, much emphasis was placed on the notion of intangible cultural heritage, based on UNESCO’s classification of customs, traditions, and beliefs as enshrined in a landmark treaty, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in 2003.

At its inception on May 27, 2005, the National Trust counted 11 founders, including Silva and Bandaranayake as well as Ashley de Vos. To oversee its activities, seven committees were formed; another committee to oversee the management of the society, came into being in 2010. Arguably, the most important of these, the Scientific Committee, branched out to eight sub-committees, dealing with areas such as monuments and sites, architectural conservation, and industrial heritage. These, not surprisingly, reflected the expertise of its founders; since their formation, they have brought together a wide group of scholars, from art historians and architects to musicologists and archaeologists.

Today, the Trust engages in several activities, and not just lectures. In 2006 it organised an inaugural tour to the Botale Raja Maha Viharaya and other areas of historical interest in the region; due to the pandemic, it has not undertaken any historical tours since 2019, when it sponsored a visit to Jaffna. It also took up several conservation projects, one of them involving the Portuguese Fort in Malwana and another Joseph Lawton’s photographs of various national heritage sites. The latter has proved useful to the researcher and archivist of 19th century British Ceylon. These projects, in turn, led to two audio-visual productions: an exploration into the history of Sinhala music based on a lecture by Tissa Abeysekara, and a similar project about the evolution of music theatre in Sri Lanka.

Perhaps, the Trust’s most important contribution has been its publications. About 20 of these have been done so far. Foraying into different fields, they have spurred interest among scholars and readers alike.

These titles include Senake Bandaranayake’s and Albert Dharmasiri’s Sri Lankan Painting in the 20th Century, Neville Weeraratne’s The Sculpture of Tissa Ranasinghe, Nishan Perera’s Coral Reefs of Sri Lanka, Gehan de Silva Wijeyaratne’s Birds of Sri Lanka, and Shanti Jayewardene’s Geoffrey Manning Bawa: Decolonising Architecture. Reasonably priced and available at leading bookshops, they underline the need to go beyond just coffee table publications of general interest.

Elsewhere, National Trusts have become a gauge of a society’s intellectual activity. In that regard the Sri Lankan National Trust may have much more potential. Though these tours, lectures, and publications have contributed a great deal, they have not been met with adequate levels of interest. Ambitious as these have been, they have not succeeded in gleaning a response commensurate with the Trust’s objectives.

In this, of course, the Trust is not to blame: there is just so much an institution can do. Yet when one considers that the British National Trust claims a membership exceeding 5.4 million, while its counterpart here claims fewer than 600, one realises the depths to which scholarly activity in Sri Lanka has fallen.

That tells us as much about our people as it does about our intelligentsia. Of late, one leading academic institution after another has been swept up by the rigours of politicisation. Scholars have increasingly turned into yes-men. Original research has become a thing of the past. What little intellectual activity there is now is underfunded and overstretched.

If Sri Lanka is to compete internationally, it must produce scholars capable of taking it to the world. Such individuals cannot thrive in a culture that rewards obeisance and acceptance over scrutiny and critique. This does not apply to politicians only, of course; people have contributed to such a state of affairs as well. In other countries, non-specialists rarely, if ever, have the last word over experts. In Sri Lanka, however, they exercise a more formative influence on the public than do professionals. This can only end badly, for everyone.

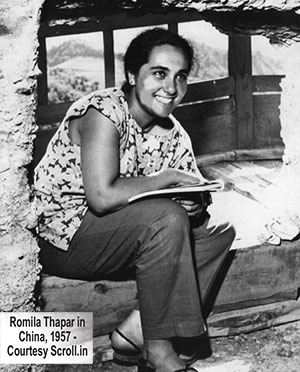

It’s not unfitting, then, for the National Trust to have chosen someone like Romila Thapar for this year’s inaugural lecture. Professor Thapar is not just the leading historian in India; she is also one of its most outspoken intellectuals. Of late, she has come out into the open, emphasising the need for nuance and rationality in the study of history.

There she has had to face a situation not too different to what we are facing: nationalist extremists have more or less monopolised discussions, turning the study of the country’s past into debates over who should be determining its future. Lost in such debates is the point that we are what we make of ourselves, that we invent the customs and traditions which we believe define us, and that these must always be placed in their historical context.

The National Trust obviously has a role to play in all this. We are caught in the midst of a severe crisis, and economic problems have taken precedence over everything else. Yet, there probably has been no better time to raise these concerns, to talk about them, to make it easier to understand our past. This is something the Trust’s founding members, especially Senake Bandaranayake and Roland Silva, engaged induring much of their lives. It is the legacy the Trust is heir to, the legacy it bears today. If it cannot live up to its own inheritance, no one can.